By The Rev Martha Macgill

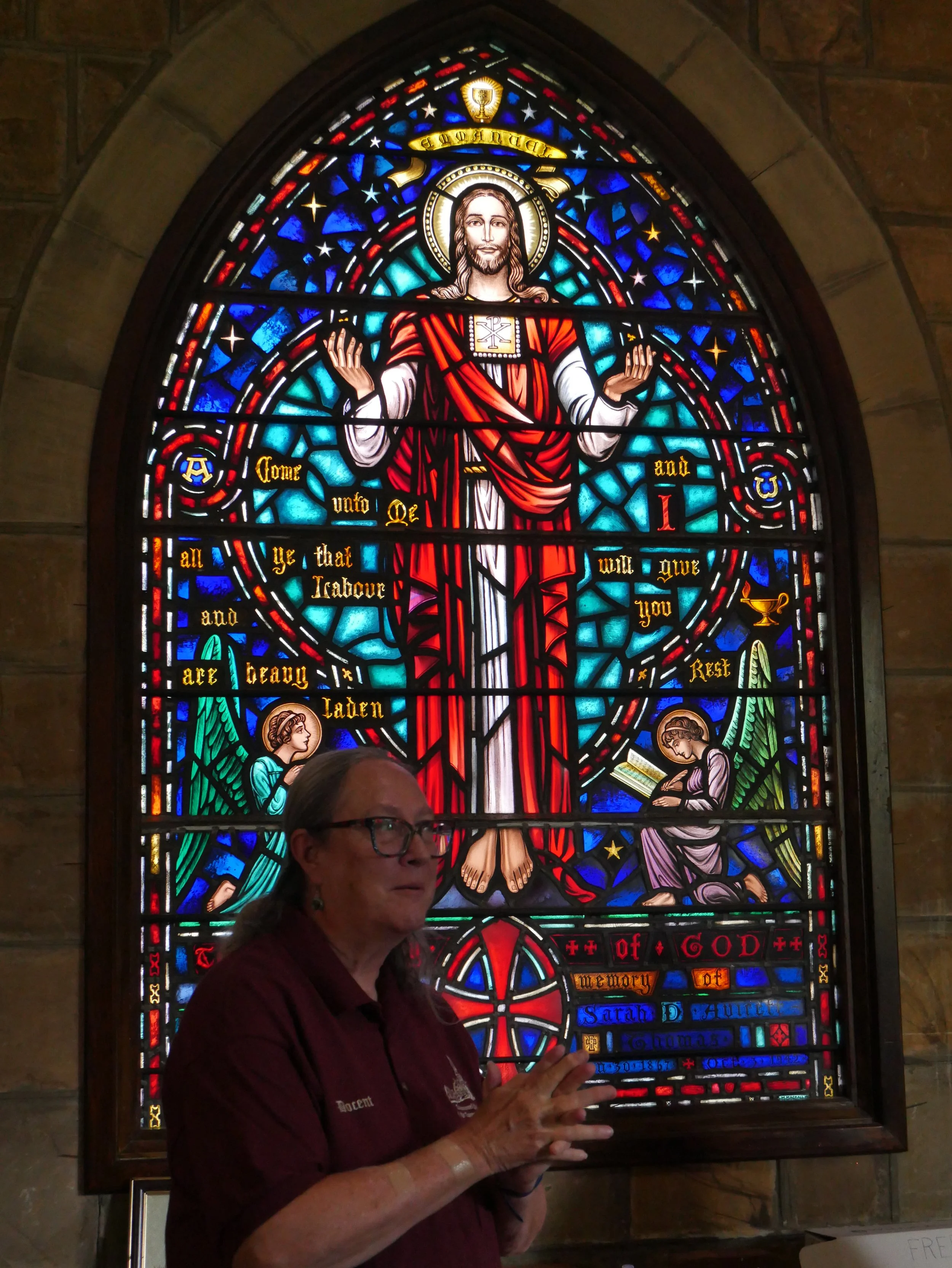

Situated at the top of the hill in the center of Cumberland, Emmanuel Parish stands for all to see from downtown and the interstate highway that cuts through Cumberland westward. Visitors are drawn to the church on the hill with the steeple. Once inside, Emmanuel tells the story of our country from its earliest times to today.

Earthwork remnants of Fort Cumberland

From the time of the earliest settlers to the region, there was a community on the hill where Emmanuel now stands. Situated at the crossroads of Native American trails and natural waterways, Cumberland and Emmanuel were known roads of freedom. As early as the 1720s, enslaved peoples from the colonies of Virginia and Maryland found refuge with the Shawnee Indians in the region. By the time of the French and Indian War, British troops found refuge on Emmanuel’s hill at Fort Cumberland. By the time of the fort, there was a worshiping congregation there. By 1851, the Gothic structure that stands today was completed and consecrated by the Episcopal Bishop of Maryland.

The Tiffany windows depicting the story of Rizpah

As one enters the historic church, one is amazed by the beauty of the stained glass. Home to three Louis Comfort Tiffany Windows, the last Tiffany window installed tells a special story. The window was installed in 1923 and depicts the story of Rizpah, a concubine of King Saul. When her sons were killed in battle, Rizpah stood all night on the battlefield with a torch, protecting her sons’ bodies from the birds of the air and beasts of the field. The benefactor of this window was Miss Elizabeth Lowndes, the daughter of the only governor of Maryland from Western Maryland, Lloyd Lowndes. Miss Elizabeth commissioned the window herself directly with Tiffany and one day, the boxes containing the window arrived. When the all-male Vestry (parish council) learned of the topic of the window—a concubine in a dramatic purple gown!—the Vestry turned down the window. Miss Elizabeth did not miss a beat. She replied to the Vestry in a strong voice: “Well, gentlemen, you might want to rethink your decision since my cousin, the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, is set to come and bless the window in a few weeks.” Needless to say, the window was installed and Rizpah’s torch shines brilliantly in the south trancept. Rizpah resembles another famous lady, Lady Liberty in New York Harbor. Miss Elizabeth was a fervent suffragette and we believe she designed the Rizpah window to give another message—a message of justice and freedom.

The location of the Rizpah window is also significant because it is placed in the location of the original gallery for enslaved people which was removed in the early 1900s. But below the floor under the Rizpah window and the church sanctuary lies another stirring story of freedom—the tunnels.

The water gate in the tunnels below the church

When the current church was constructed in 1851, it is believed that the original Fort foundations underneath the church were used as a stop on the Underground Railroad. African-American oral history of Cumberland tells us that the Rev. Hillhouse Buel, the Rector of Emmanuel then, was from a known abolitionist family in update New York who married the daughter of a North Carolina abolitionist. It is believed that he and his Sexton (or church custodian, which local oral history identifies as Samuel Denson) were the conductors of the Underground Railroad at Emmanuel.

The Underground Railroad, according to oral history, ran in this way. Enslaved people traveled hidden in wagons on the National Road or in boats on the C and O Canal. Once arriving in Cumberland, they hid in what was called Shanty Town at the terminus of the C and O Canal. At night, there was an agreed upon signal that it was safe to come up the hill to the church. In the middle of the night, the Sexton of Emmanuel would ring the church bell an incorrect number of times. For example, if it was 2 am, he would ring the bell three times. That was the signal for the enslaved to use the cover of darkness to climb the hill to the Water Gate at Emmanuel, come through the tunnels and travel underneath the church to a hidden room. Once it was deemed safe to move further, the enslaved individual or families were to travel underground through the tunnels that went under the main streets of Cumberland to the church Rectory. Again, those seeking freedom would stay in hiding and would be cared for until it was safe to move across the Mason-Dixon Line to freedom.

Today, when one visits Emmanuel, one can feel the palpable sense of its history, particularly when one goes down into the tunnels. One can sense the lives lost and the lives gained in that space. And the hope that freedom is a true hope and reality.

To schedule a tour of the Church visit their website or email Rev Martha at soulspacecumberland@gmail.com

Rev Martha leading a tour