The Hammons Family (Library of Congress)

West Virginia’s famed old-time folk family, the Hammons, live in both the mythologies and histories of Appalachia. The Hammons Family settled in West Virginia on the fringes of society in Webster and Pocahontas County. One standout figure, Edden Hammons (1874-1955), is known as one of the most prolific fiddlers of his time. He has been immortalized in county annals–as a nine-year-old who once outplayed an older fiddler in Webster County, embarrassing the man in front of his audience and causing him to storm out mid-concert–, fictional short stories–like G.D. McNeill’s tale “That Hammons Boy” describing a young boy becoming a virtuoso–, and oral memory–such as the folk poem Hammons and the Ass. Other notable Hammons include Burl (1908-1993) and Currence (1898-1984), who are among the few central West Virginia old-time folk artists of their time to be recorded. Through the Hammons and their music, we gain a peek into the history of Appalachian old-time music and its diverse sources. Burl and Currence learned many of their tunes from Black folk artists like Grafton Lacy of Braxton County. Lacy is no exception; Black artists have made many founding contributions to the genre. In the stories of Appalachian folk music their role is often obscured, or in the case of Lacy, sparsely mentioned. The hidden history of old-time music emerges from in between the lines of the sound itself, with its origins ranging from the British Isles to West Africa.

Folk music in Appalachia has often been described as having mainly Scots-Irish and German roots. This ties closely with the notion of early Appalachian settlers being of mainly Scots-Irish and German descent. The Hammons family themselves came from Scots-Irish stock, and many married descendants of German settlers. The traditions of these ancestors are preserved in old-time music. Old-time fiddling often employs tunings and structure closely related with German and Scots-Irish predecessors. In central West Virginia, a Germanic structure of changing the key of a piece from the first part to the second is prevalent. Cross-tuning, or adjusting the tuning of the strings of a fiddle resulting in a more unconventional sound, and playing in modal scales for a similar result, are tendencies in Scottish and Irish fiddle music that date back to pre-classical techniques. Appalachian folk pieces like “Greasy Coat,” a tune in Edden Hammonds’ repertoire, continue the tradition of cross-tunings and alternative scales that remain rare in modern music. Beyond how a tune is played, its name may betray its origins: such as “Two-Step Schottische” (German for “Scottish”) and “Rocky Road to Dublin.” Old-time fiddle music is often dance music and Appalachian folk dances and the tunes for them include German waltzes and Scottish-Irish reels and hornpipes. Many European practices that have disappeared elsewhere remain in West Virginia, such as the separation of instrumental music and singing as in old Irish music, the Germanic instrument known as the dulcimer, and Scots-Irish bowing styles. These roots have been especially preserved in the Appalachian forest as separation from a wider world allows distinct ethnic cultures to flourish.

Listen to Burl Hammons, Greasy Coat

Grave of Grafton Lacy (Paula Harper via Find a Grave)

The example of Grafton Lacy, a Black fiddler and banjoist, provides clues to the interracial exchanges that created old-time music. Burl Hammons tended to hang around a barber shop near a railyard on Tea Creek that was a hotbed of music. There he would visit Lacy, described by the Hammonses as a railroad worker who lived on the Williams River. From Lacy, Burl learned tunes like “Darky’s Dream” and a three-fingered style of playing the guitar. Another folk musician, Brooks Hardaway, would go with Lacy to Granny’s Creek in Braxton County where many formerly enslaved people resided to hang out and play music all week long. Lacy was just one of many conduits in the exchanges between African American and European folk traditions.

Listen to Burl Hammons, Darky’s Dream

Black artists have deep connections with folk music and Appalachia. Before the Civil War, enslaved people often served as the musicians for White social functions–ranging from plantations to Appalachian resorts–and evidence of the ability and affinity for playing the fiddle was commonly listed in fugitive slave postings. In the late nineteenth century, Black migrants came to Appalachia following the railroad, logging, and coal industries in places like Cass, bringing with them their music and instruments. Whether freed or enslaved, Black musicians such as Grafton Lacy interacted with White Appalachians such as Burl and shared their musical heritage.

The tune Lacy taught Burl, “Darky’s Dream,” hints at another source of Black influence: minstrel shows. Minstrelsy, the tradition of white musicians in blackface, has complicated connections to Black folk culture. White minstrels drew from, in order to mimic or mock, the plantation bands of enslaved musicians. While minstrelsy was a racist practice of ridicule, not all tunes were inauthentic imitations and many came from genuine African-American sources. The tune that popularized the character of "Jim Crow," pioneered by the "father of American minstrelsy" Thomas Rice, was first overheard from an enslaved singer. After the Civil War some minstrel groups were all-Black or included Black musicians, allowing more direct African-American influence to the songs and playing styles they featured. The term “darky” in Lacy’s tune is a derogatory term to stereotype Black southerners and was a common archetype portrayed by minstrels, sometimes called “Old Darky.” The tune resembles the known minstrel song, “Essence of Sugar Cane.” Lacy’s adoption of the tune makes it hard to define as strictly minstrel or strictly African-American; wherever the initial source, it is a product of the intertwining of minstrel music and Black folk tradition.

Burl's brother Sherman (Augusta Heritage Center)

Throughout the nineteenth century, minstrel songs reached Appalachian Whites and entered their repertoire. “Jump Jim Crow,” traced directly back to a black musician via minstrel Thomas Rice, is also in the catalog of Braxton County fiddler, Melvin Wine. Minstrel tunes spread to Appalachia through Black and White musicians picking up and sharing them, minstrel shows, and boats. Riverboat minstrels often traveled down the Ohio and the Big Sandy Rivers between Kentucky and West Virginia. The Hammonses' Kentucky heritage traces back to the same Big Sandy region, where both rivers meet. The Hammonses were subsequently influenced; former minstrel tunes in their family include “Turkey in the Straw,” also known by its minstrel title as “Old Zip Coon,” and songs like “Rock Old Liza Jane” and “Sandy Boys” have lyrics about old ‘massa.’

Listen to “Liza Jane” by Sherman & Lee Hammons

Black fiddlers drew from traditions predating their arrival in America. While the fiddle is evidently European, the goje is not. The goje, with a gourd body, a bow, and one horse-hair string, is one of many West African stringed instruments resembling a violin. This instrument was approximated by enslaved people throughout the United States, who would use bodies that ranged from gourds to cigar boxes, to recreate their ancestral fiddle. Music and dance were languages of resilience for enslaved populations, with inventive fiddles and fiddlers as centerpieces. The banjo itself has uniquely African origins. Described by slave owners as the “banjar,” an instrument resembling those like the West African bolon, akonting, kora, and more first appeared in the plantations of the Caribbean. The banjo made its way to old-time music solely because of Black musicians.

Enslaved people additionally brought rhythms and tones from Africa that now compose American music as we know it. Syncopation, the emphasis of off-beats, is an unmistakable rhythmic feature in Appalachian old-time fiddle bowing. In African music, time signatures are often combined to create simultaneous rhythms in a complex, syncopated way. This gives African-American music its definitive “hot” element. Southern fiddling’s “hot” factor differentiates it from the more stately New England fiddling, with a spice that impels you to tap your feet. Not only did Appalachian old-time fiddling borrow hot, syncopated rhythm from African influences, but also dances modeled off the rhythm’s frenetic energy. A “breakdown,” a common type of old-time tunes, is a dance term with African-American origins in corn harvest celebrations on the plantation. Additionally, when enslaved people played and danced European dances, they adapted African rhythmic and music traditions in a way that has also spread to Appalachian folk dancing. Compare the following tunes: “Petronella” (a New England tune) and “Poca River Ride” (a West Virginian tune).

While European music is organized with seven-note scales, African music works on pentatonic and hexatonic (five- and six-note) scales. In European music, the focus is on harmony and resolution, whereas the pentatonic and hexatonic scales enable dissonance. African musicians use these scales’ relative simplicity to toy with variation, gliding between notes by their voice or instrument. “Blue” notes come from a combination between African and European melodic schemes, where musicians find the more dissonant notes in between the traditional European scale. Old-time Appalachian fiddling reveals its African heritage via these Blue notes as well the technique of sliding between notes.

Despite the fact that the sharing of cultures produced old-time music, Black musicians faced overwhelming racial prejudice. The recording industry of the 1920s, eager to commercialize old-time music, segregated the shared genre into the Black and White categories of “race” and hillbilly.” With an eye for White markets, the industry promoted minstrelsy to ridicule Black folk artists. Additionally, White folk artists were ingrained in an anti-Black society. The Hammons family were reportedly a part of the Ku Klux Klan and some participated in the Klan’s violence. Despite anecdotes about Edden Hammons rebuking them, he was still known as a member.

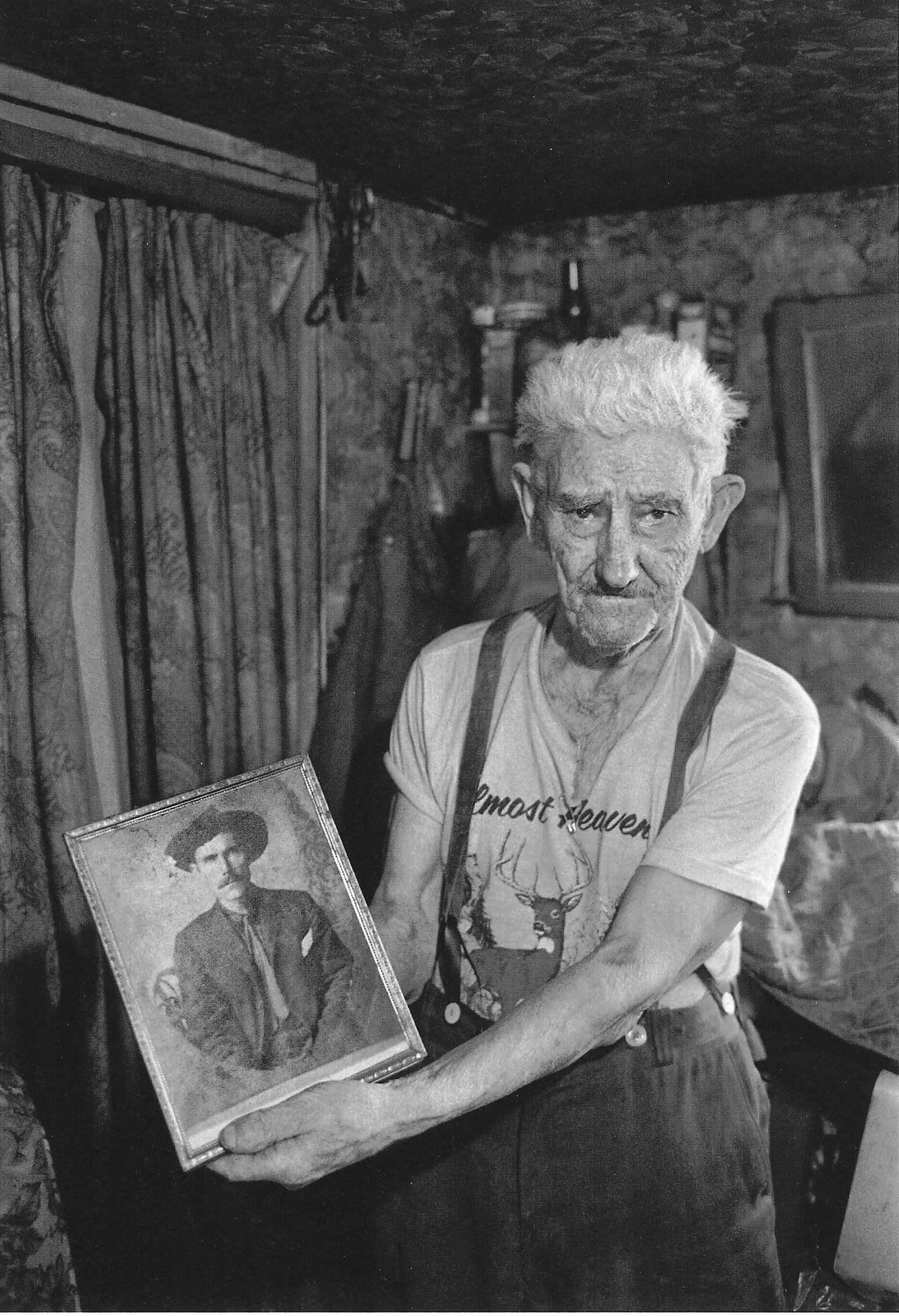

Smith Hammons with a photograph of his father Edden (Mark Crabtree)

One popular story about Edden Hammons is that of his first fiddle. So eager to learn, he took a gourd and carved it into an instrument. Drawing from, or at least symbolically resembling West African tradition, the Hammonses are inseparable from the Black influences on their music and old-time in general. Prejudice and the marginalization of African-Americans has complicated their proper accreditation in the genre. These ties are evident in the music itself, however, which has often been a site of sharing for diverse communities. The fiddling traditions of the Scots-Irish and African-American combined in a region where physical isolation cut them off from the outside world and encouraged interdependence and musical cohesion. The massive contribution of Black artists is only vaguely hinted at in oral histories of old time music: the spare reference to those like Grafton Lacy for example. However, it is preserved in the auditory history, where instruments, rhythm, and melody reveal rich, intercultural roots.

Read more about music traditions in the Appalachian Forest in our Homespun and Handmade exhibit.

Learn about Black culture in the region in our previous exhibit Creating Culture.

Bibliography:

Blaustein, Thomas. “Traditional Music and Social Change: The Old Time Fiddlers Association Movement in the United States,” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, 1975.

Chase, Gilbert. America’s Music. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. 1955.

Conway, Cecilia. African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia: A Study of Folk Traditions. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1995.

DjeDje, Jacqueline. “Appalachian Black Fiddling: History and Creativity,” African Music: Journal of the International Library of African Music 11, no. 2(2020):77-101.

Fleischhauer, Carl and Alan Jabbour, ed. The Hammons Family: A Study of a West Virginia Family’s Traditions. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1973, 2018 [1973].

Fuller, Christopher. “The Roots of the Banjo,” Black Music Project.

Jabbour, Alan, ed. American Fiddle Tunes, Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1971.

Lott, Eric. “Blackface and Blackness: The Minstrel Show in American Culture,” in Inside the Minstrel Mask: Readings in Nineteenth-Century Blackface Minstrelsy, eds. Annemarie Bean, James Hatch, and Brooks McNamara, Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1996.

Milnes, Gerald. Play of a Fiddle. Lexington, KY: The University of Kentucky Press, 1999.

Minton, John. “West African Fiddles in Deep East Texas,” in Juneteenth Texas: Essays in

African-American Folklore, eds. Francis Abernathy, Patrick Mullen, and Alan Govenar, Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 1996.

The Traditional Tune Archive. “Darkey’s Dream,”